Mao’s Marx and the Chinese Civil War

By Emmanuel Harish Menon // Posted on: Oct 18, 2021

The modern-day ideology that governs the political organisation of the People’s Republic of China bears little resemblance to the philosophy first posited by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in the 1800s and why should it? Even China’s first introduction to Marxism, which came in the form of what is now known as Maoism, was specifically catered to work amid the Chinese Civil War took more from Leninism (itself a localised version of Marxism) than it did from Marxist ideology. It is important to note that there have been “seismic changes in policy, legislative enactments, and application” since Mao Zedong’s rule came to an end at the time of his passing in 1976. Mao’s localised interpretation of Marxism-Leninism is one of the core factors contributing to the Chinese Communist Party’s victory over the Guomindang in the Chinese Civil War.

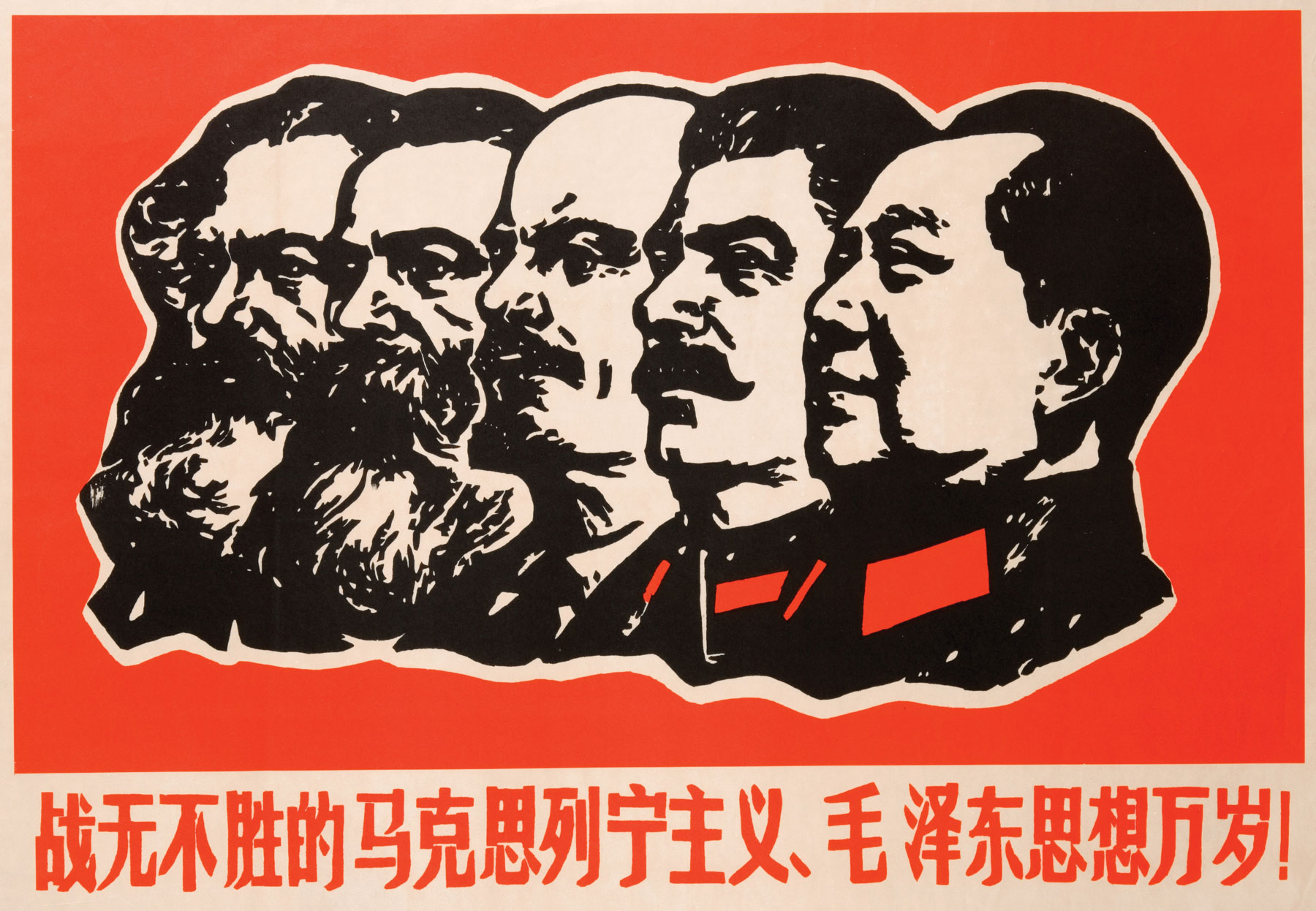

Figure 1. “Long Live the Invincible Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought!” (1967), Unknown

Background

Marxism

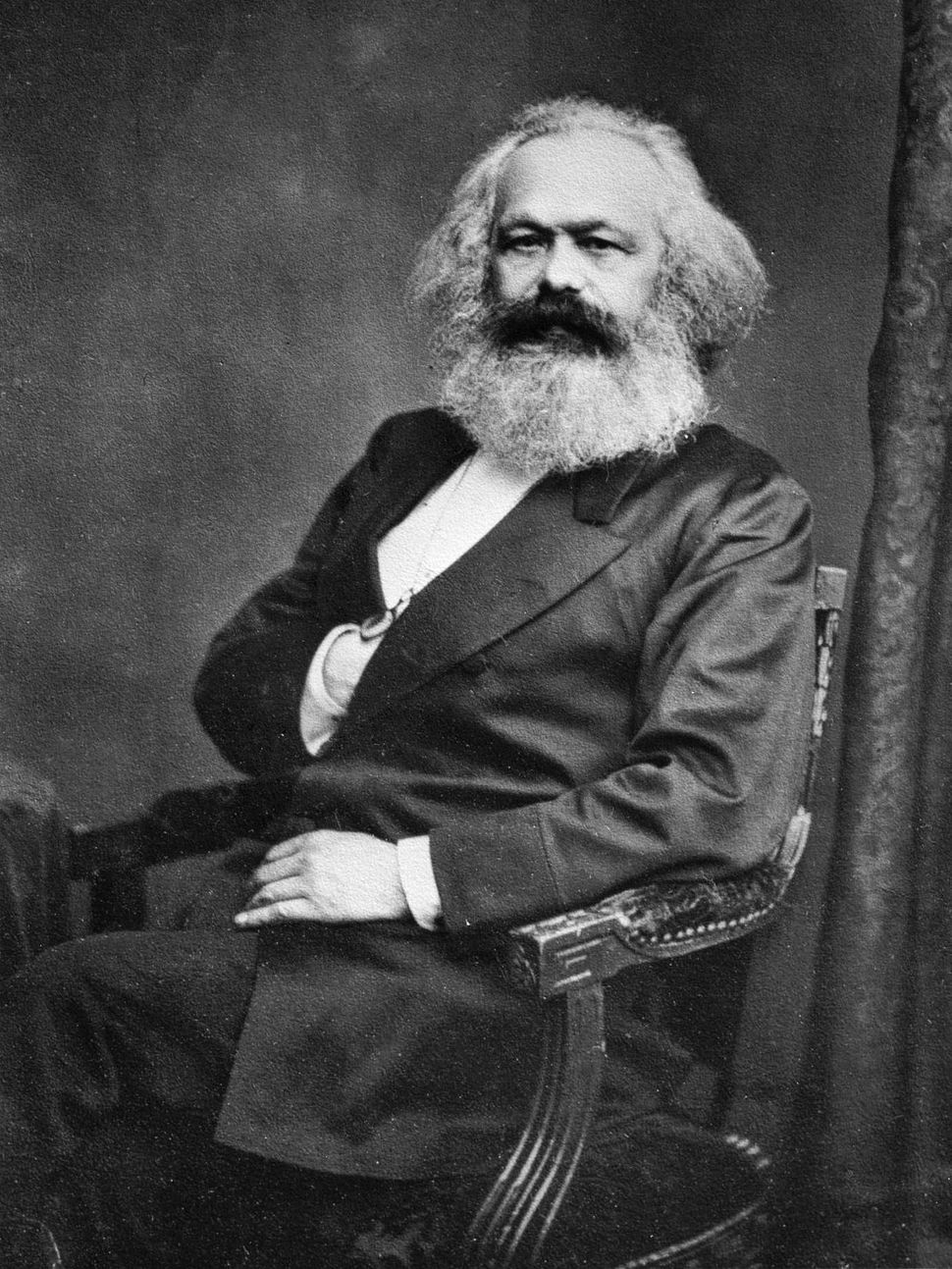

Figure 2. “Karl Marx” (1875), John Jabez Edwin Mayall

Marxism is a philosophy first outlined in detail by Karl Marx, that looks at societal, political and economical problems through the lens of conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. In a modern sense, the bourgeoisie is seen as the capitalist ruling class—individuals in class that have often accumulated large amounts of capital by exploiting the proletariat to further solidify or improve their economic position in society. The proletariat, on the other hand, are the working class, who do not own the means of production, and whose only means of surviving is by selling their labour-power for a wage or salary. This struggle is at the core of classical Marxist philosophy.

Leninism

Figure 3. “Vladimir Lenin” (1920), Pavel Semyonovich Zhukov

Lenin became the leader of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1898. This organisation was a political party that united various factions of the Russian Empire on the concepts and ideology put forward by Marx’s writings. While initially, it appeared that Lenin would stick to the core philosophy of classical Marxism, by the time he came into power, it became clear that his philosophy deviated from Marx’s. While both believed that the proletariat was exploited under capitalism, Marx believed that the transition from capitalism to communism would come immediately through the proletariat gaining class consciousness—that is, the understanding that they were being exploited, solely to the benefit of the capitalists—and overthrowing the bourgeoisie. Meanwhile, Lenin believed that class consciousness “could not be expected to manifest itself as a “reflex” of prevailing economic conditions”, and that transitioning Russia to a socialist system—where the means of production were state-owned—would be necessary before completing the evolution into communism.

However, in 1921, as a response to the famine and unrest that began rearing its head—which led to Russia’s GNI falling to a third of the level it had been prior to the start of the Russian Civil War—Lenin instituted the “New Economic Policy”, whereby the surplus of the peasantry’s farm produce was not confiscated and redistributed by the state but was instead (for a fee) retained by the peasantry to be sold. They were also allowed to hire labourers. This policy essentially pivoted the initial state-socialist organisation of the economy into a state-capitalist organisation of the economy.

Maoism

Lenin saw that his revolution was failing, and decided that he needed to inspire his people by showing them a successful revolution. So the Comintern decided that China, itself in a state of political turmoil from the fall of the Qing dynasty and the increasing regionalism after Yuan Shikai’s death in 1916, would be the perfect place to foment revolution. This led to the formation of the Chinese Communist Party in 1920. After Mao joined the CCP’s and GMD’s “united front”, he quickly rose to become the face of the party.

The differences between Maoism & Marxism

Figure 4. “Unknown” (n.d.), Unknown

It’s never been clear as to the extent of Mao’s academic understanding of Marx’s teachings in his early days as a young revolutionary leader because much of his early writing has been modified retrospectively. In fact, there is more clear evidence of him being influenced by Sun Yat-Sen’s (who was the GMD leader at the time) ideas, especially the “Three Principles of the People” than there are of him referencing Marx directly during this period. The Comintern did not have a problem with this, as one of the purposes of getting China to revolt was to prevent capitalist nations that relied on imperialism to exploit the markets and resources of developing nations, which would, in turn, embolden the international proletariat to overthrow the forces exploiting them during the seemingly inevitable international revolution.

Despite China being just another piece in the Comintern’s plans, Mao saw the nation as an integral part of the international revolution. But 1920s urban China largely consisted of people who would be considered bourgeoisie. Mao recognised this problem and redefined the meaning of the proletariat to include intellectuals, students and petite bourgeoisie. Mao also added peasantry to his definition of the proletariat, This gave the CCP numbers for their overthrow of the ruling class, despite the essence of Marx’s definition of the proletariat (workers whose only possession of economic significance is their labour-power) being lost in translation.

Even in Mao’s writings during the second phase of the Chinese Civil War, Mao reaffirms his commitment to Sun Yat-Sen’s Three People’s Principles saying “our Party is ready to fight for their complete realization”. Any Marxist ideology was secondary to this primary goal and only served to advance closer to realising these original principles. Even in 1949, as Mao acceded to power, he allowed the continued production of commodities by private owners, allowing them to hire labourers. Ownership of the land was and by large the same, with the redistribution only landowners who were members of the GMD.

Mao was a talented strategist, who understood that utilising Marxist ideology without adapting it to suit the needs of the CCP would mean that the revolution would fail. His adaptations of the ideology to mobilise the peasantry and intellectuals were key to the success of the CCP in the Chinese Civil War.

Bibliography

Tagged with:

history

/

school