Guan Wei's Two-finger exercise no.4

By Emmanuel Harish Menon // Posted on: Apr 17, 2023

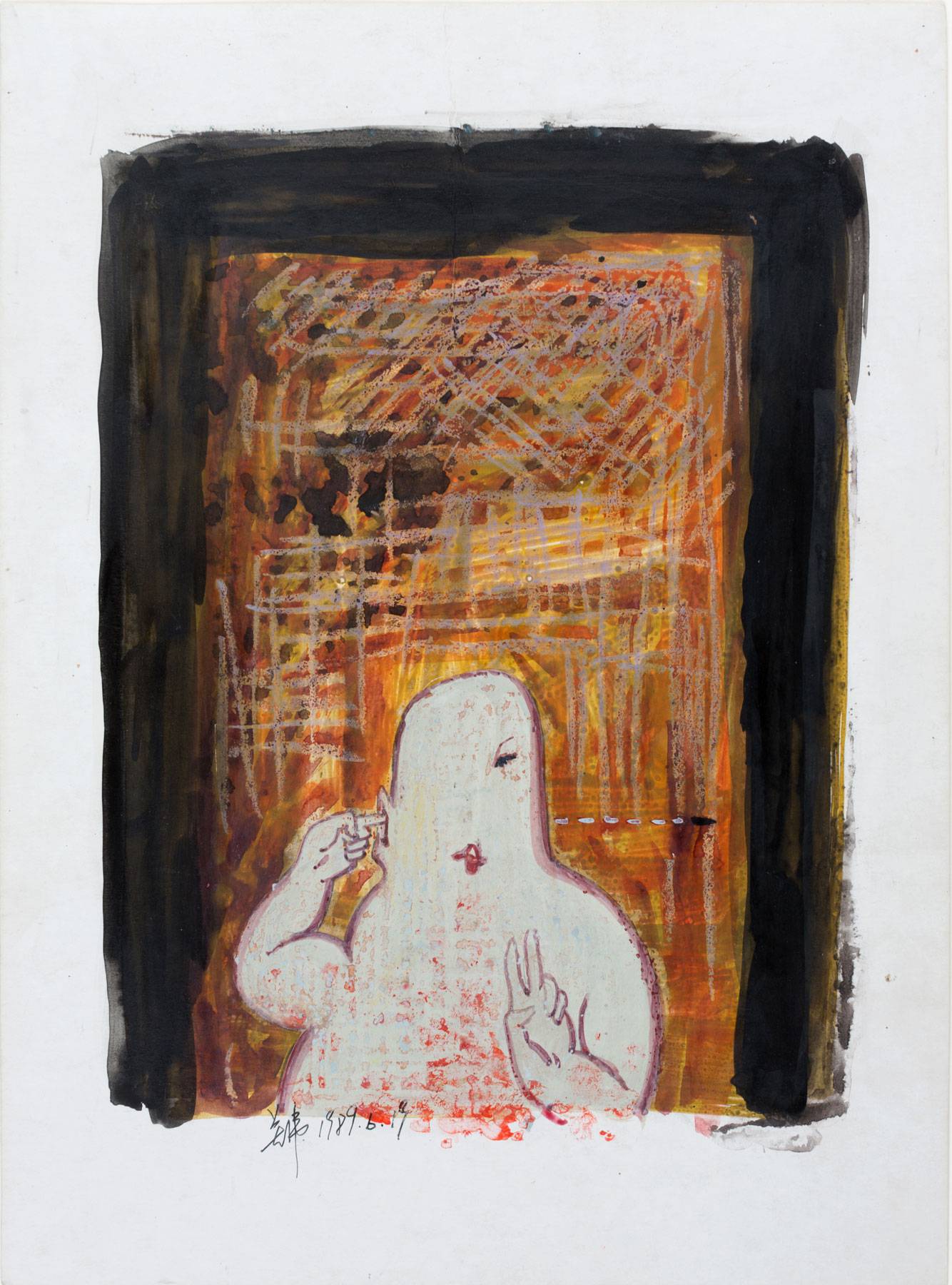

Two-finger exercise no. 4 (1989) — Guan Wei

Guan Wei // China, 1989

Guan Wei was born in Beijing in 1957, a descendant of the Manchu—rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, the last Chinese imperial dynasty—who, in their 276 years of rule, ushered in an era of rich artistic culture. One specific group of Qing artists—loyalists of the previous Ming dynasty, known as individualists, who often made eccentric, abstract political pieces protesting against the Qing Dynasty—seems to have influenced Wei’s work, both in content and style, especially much of his early work, which consists of blunt depictions of the horrors taking place in 1989 China—during the Tiananmen Square protests—in an expressionist, surreal style.

Wei cites the support and encouragement of his father—who was an actor in the Beijing opera—as one of his primary inspirations for pursuing his passion for art. As a child, Wei often went to the opera to watch his father perform, where he recalls being astounded by the emotional depth and realism of the performances, as well as the colours pervading the entire space, saying “the Beijing Opera, the colour and gesture, is there in the surface of my pictures, but the deeper human aspects of personality are behind my pictures”.

After leaving Beijing for an artist residency at the Tasmanian School of Art in January 1989, Wei returned to China in early April, just as student protests began over the suspicious circumstances surrounding the death of Hu Yaobang—a high-ranking CCP party member who often advocated for more stringent legal limits to the CCP’s dictatorial sphere of influence. Over the coming months, events would slowly escalate, as the movement gained public support and broadened in scope, targeting corruption as well as advocating for freedom and democracy. Eventually, on the 3rd of June in 1989, martial law was declared in Beijing, and the CCP sent in the military. By the 5th, the military had reached and cleared Tiananmen Square of any remaining protestors, taking the lives of thousands—estimates vary due to the CCP’s retroactive obfuscation of the events that took place—and wounding countless others as they marched towards their goal.

Two-finger exercise no. 4 was painted on the 15th of June 1989, approximately two weeks after the military had taken the square. Wei painted on letter-sized cards with gouache—a painting technique dating back to 4th century Egypt that essentially combines watercolours with an additional binding agent, resulting in an opaque watercolour when dry. Everything about the image communicates the chaos and indiscriminate violence imposed upon the Chinese people during this time—particularly the burning building taking up much of the background—with the half-faced individual depicted in the picture, contorting their left hand into the two-fingered “V” known as the “Victory Salute”, even as their right hand contorts into a finger-gun pointed directly at their own head.

Elements of Composition

colour

The background of this piece is dominated by analogous muddy pigments of orange—the colour of fire—including an orange-yellow and an orange-red, colours contrasted only by the muted greyish-white of the person in the centre, as well as the thick black frame that they are forced to exist within, emphasising this feeling of claustrophobia in an unfamiliar, chaotic environment. Every colour in this piece is dull except for one splash of saturated colour across the very bottom of the piece—the blood patched across the person’s torso remains a bright red, drawing the viewer’s eye. This is aided by the slight, gradual saturation in the colours of the dancing flames, which seem to surround and envelop the person—a saturation seen especially in the brightness of the orange-yellow crowning the person’s head. Every use of colour in this piece is intentionally designed to emphasise the innate chaos of the authoritarian violence and destruction depicted in the background of this piece, which, in turn, contrasts the emphasised tranquillity of the person ending their own life, in pursuit of the hope of freedom from the effects of the iron grip of an unseen, totalitarian ruling class.

texture

The element of texture is integral to the aforementioned chaotic feel of this piece. The uneven thickness of the downward brushwork of the black frame assists in drawing the eye down to the main point of interest of the piece—the person, who is themselves textured smoothly with no visible brushstrokes, communicating a sense of peace and calm. This, in turn, contrasts with the bootprint-like texture of the blood and grime—subtly overlaid on the person’s body, getting far more opaque as it reaches the bottom of the frame—as well as the crude grey lines forming a building, which has been etched over the smoking, raging flames surrounding the person. Amongst all this chaos, the eye is repeatedly drawn back to the smooth, centred individual taking their own life—perhaps in protest at the state of the world surrounding them—forcing the viewer to contemplate the clear juxtaposition between serenity and anarchy, daring them to rationalise the contradictory yet seemingly harmonious existence of the two.

Interestingly, Wei utilises both shape and form in this piece as complementary elements to further drive home the contrast between the person and their environment. While the piece itself is mostly two-dimensional—the doorway, building, and flames are all presented as flat objects without any depth—Wei adds a subtle shadow surrounding the inside of the individual’s outline, particularly on the left side of the subject’s face, endowing them with form by way of Wei’s suggestion of both depth—in the subject’s separation (and potential alienation) from their environment—as well as a sense of rational coherence amongst seemingly irrational expressionist scrawlings.

Principles of Composition

balance & symmetry

One of the compositional principles subverted and experimented with in this piece is the principle of balance and symmetry. Looking at the image above, it becomes clear that this piece is neither vertically nor horizontally symmetrical, with additional visual elements—the subject’s singular eye and lipstick-adorned lips, as well as the bullet and its trail—present on the bottom right quadrant of the image, elements which are not found on the bottom left quadrant. The hands of the subject have also been contorted in a very unnatural, odd way on both sides of the image. This slight breaking of otherwise perfect vertical symmetry places further emphasis on these elements, drawing the viewer’s attention further into the piece. Furthermore, these elements help balance the piece against the plumes of black smoke in the top-left quadrant of the flame, while the individual in the bottom quadrant of the piece balances against the scaffolded building in the top quadrant. By making the image balanced while subtly breaking the vertical symmetry of the artwork, Wei draws attention to the specific parts of the image that he wants to highlight.

unity & harmony

The individual presented in Two-Finger Exercise No. 4 exists in direct contrast with everything else in the piece, residing only within the bottom half of the image, dwarfed in scale by both frame and flame, compounding upon the sense of overwhelming, all-encompassing anarchy presented in the subject’s surroundings. Here we see Wei’s subversion of the compositional principles of unity and harmony in favour of a sort of harmonious discord, wherein harmony is found in the analogous colour scheme of the flame, painted almost randomly with the brushstrokes of the flame seeming to vary wildly in size, shape, and direction. This itself exists in direct opposition to both the strictly directional brushstrokes used for the black frame, as well as the smooth, dull white exterior of the individual, emphasised by the thin contour of the outline and shadow surrounding them.

Bibliography

Tagged with:

analysis

/

school